I never originally planned to dive into the world of Geographic Information Systems (GIS). While I had used ArcMap a few times during the second year of my civil engineering undergrad, I didn't understand the full scope of the software and systems, as we only used the tool for extremely basic tasks. We quickly moved on, and GIS skills weren't officially needed for the rest of my time at UofT — though they came in handy for some courses, which I'll get into.

Geotech? Is that like soils and surveying?

Even when I was officially selected to go on an army training course to become a reserve geomatics technician, I didn't fully understand what I was getting into. Since the army uses the term geomatics technician — or more commonly, geo-tech, which is not to be confused with the other geotechnical engineering — I thought I was going to learn mainly about surveying skills. In my defence, basic surveying was already part of our responsibilites as combat engineers, since they are essential skills for setting up our bridges. So learning how to make maps was slightly unexpected to me.

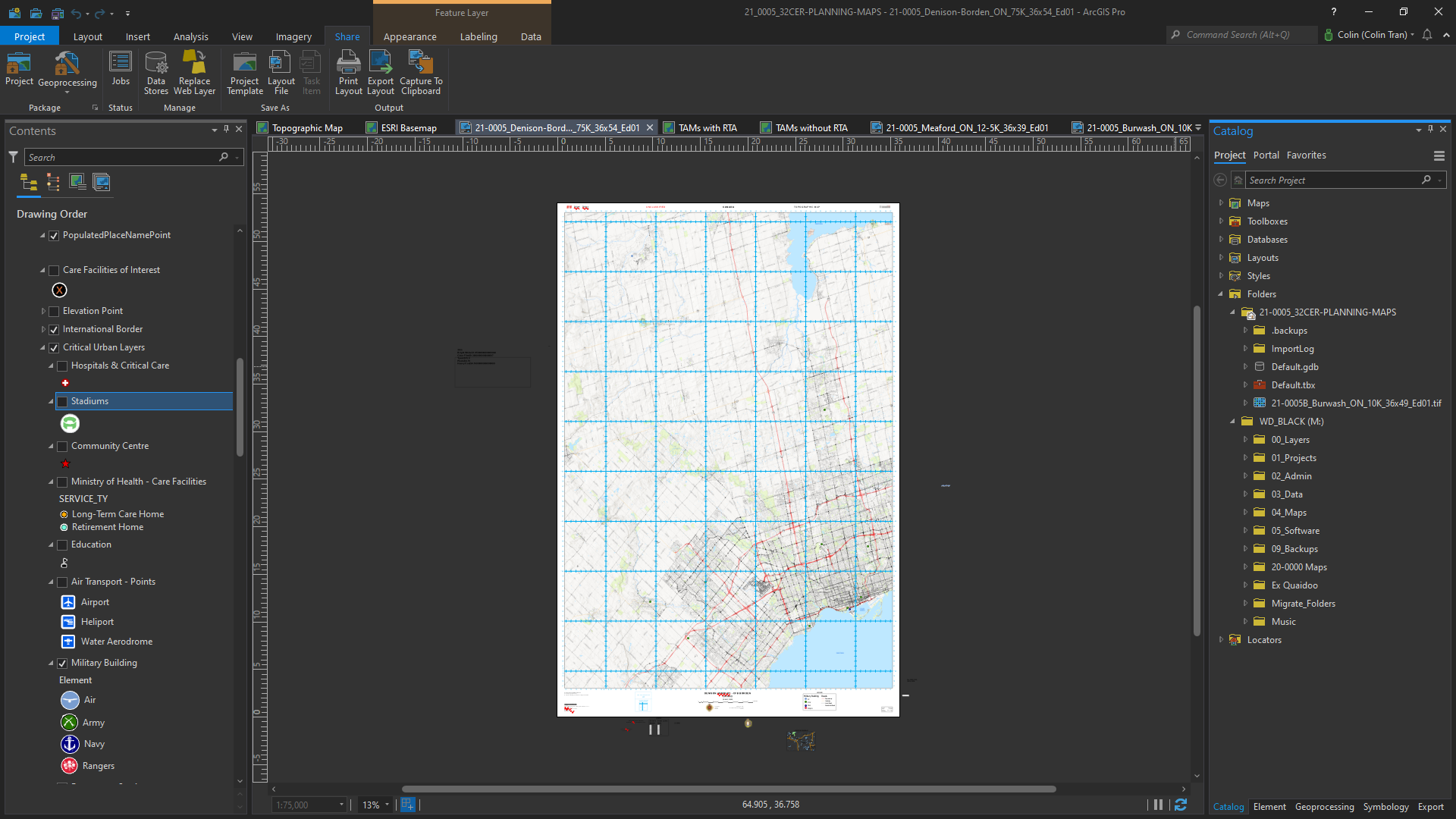

So in the summer of 2019, I drove off to spend 5 weeks in CFB Valcartier, located about 20 minutes north of Québec City, where I would be a candidate on what was essentially a crash course in how to employ ArcMap in a military environment. Unfortunately, the scope of the course was very narrow; the usual training that regular force members go through lasts 2 years, including military specific courses and a 2 year program at Algonquin College. Aside from learning the very basics of the ArcMap software suite and the standard army formatting for maps, we learned how to set up and manage the associated equipment (large format plotters and scanners, network-attached storage, switches, etc.). It was unfortunate because in those 5 weeks, I had essentially barely scratched the surface.

I don't even know what I don't know

After returning home, I decided that I wanted to learn more, because even though I didn't gain much from the training course, I wanted to treat it as a primer and dive deeper into cartography and GIS. So the first thing I did was ditch the venerable and aging ArcMap for ArcGIS Pro. The modern version of the software was significantly more powerful and had many quality of life features that made using it more enjoyable. Additionally, ArcGIS Pro has many integrations with online services, providing more data and imagery to work with. It's not all perfect, however. In fact, the earlier versions around 2.0-2.4 were super buggy and were missing important functions. For my uses, the software seems to have stabilized.

Edit Jan 2022: Never mind, basic functions in ArcGIS Pro, like multi-threaded geoprocessing, seem to be broken on Windows 11, at least for me.

I made use of online resources, from GIS themed subreddits and official ESRI forums, to gis.stackexchange.com posts. The biggest help I had, however, was working under a fully qualified geomatics technician with over 10 years of experience in the army. The Master Corporal — and now, Sergeant — in question taught myself and the others in my unit more about data and raster analysis, and about map design. In the end, I became much more comfortable working with and transforming data, as well as adding my own flair to my maps.

Wait my products are actually being used?

In January of 2020, I ended up in a full-time army position where I was tasked with assisting the above-mentioned Master Corporal. During this contract is when I would learn the bulk of my GIS and cartography skills. When the pandemic started in March of 2020, my contract was extended and I would spend the next 5 months providing mapping and data services to the 4th Canadian Division's headquarters, which oversaw the military's response to COVID-19 in Ontario.

During those months, I would create paper maps of areas around Ontario for soldiers and commanders deployed on Operation LASER to use. I also assisted in the creation of online portals using ESRI's ArcGIS Online, such as this dashboard, that helped keep track of COVID cases and statistics within the military's area of responsibility. As part of keeping the online portals up to date, I created scripts using Python that would scrape other websites and sources, automatically updating our pages, allowing ourselves to work on other assignments.

At this time, I also realized just how weird Python library names could be. Like beautifulsoup4, pandas, and fuzzywuzzy.

The operation started winding down by summer's end, and my contract finished just in time for me to return to school for my final 2 semesters. Unfortunately, both semesters would be conducted fully online. While in school, I would continue army activities on a part time basis, providing geomatics services in between my hectic university schedule. Fortunately, the data I was working with was unclassified, so I was able to do some work from home on my own computer — which is significantly more powerful than the laptops we had — instead of heading to the armoury.

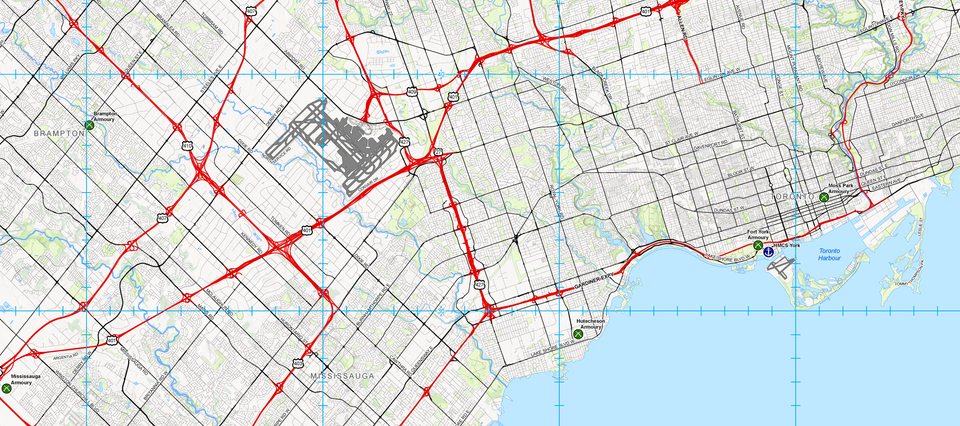

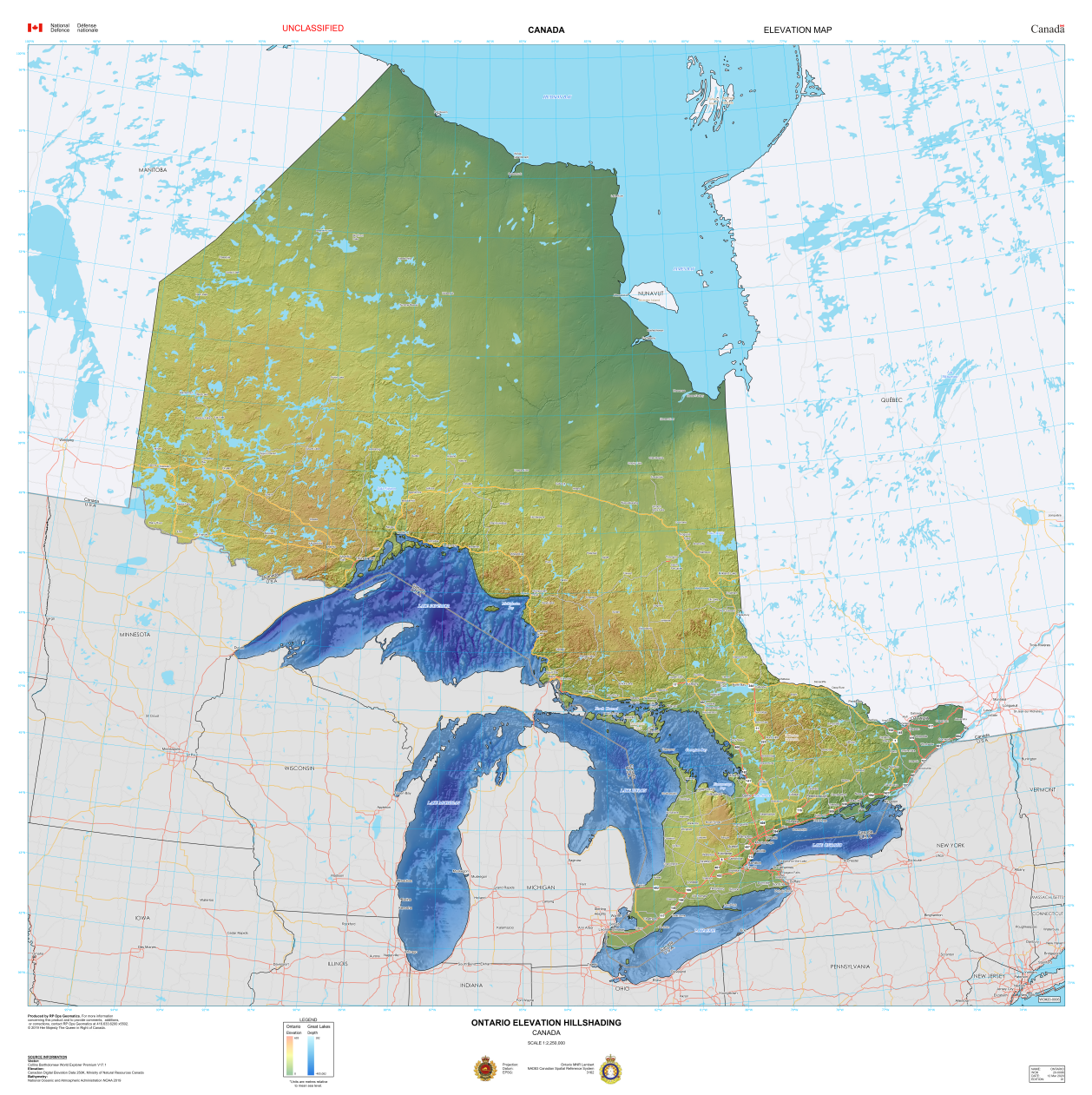

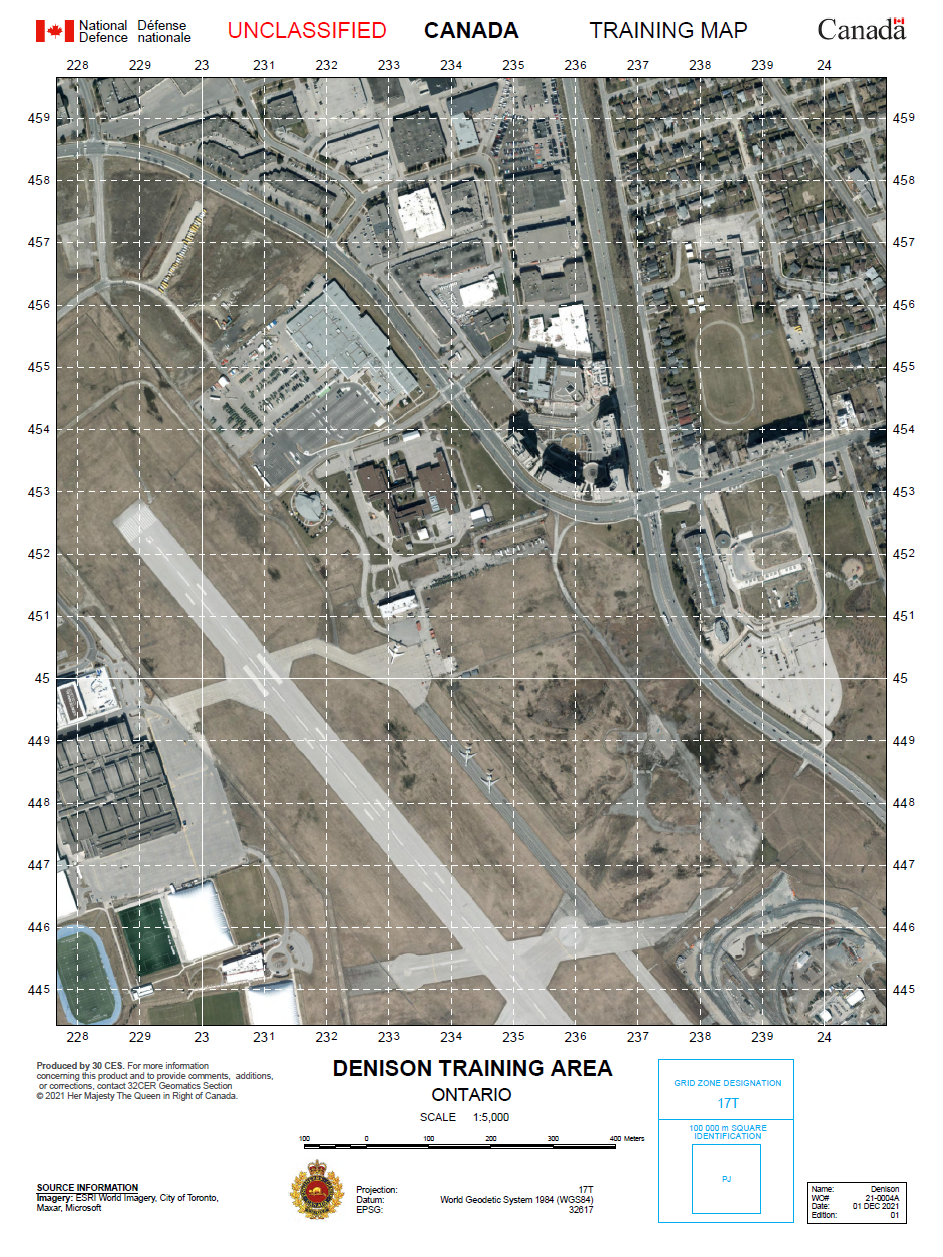

Since our maps are commonly used for briefings and planning, they tend to get very large, like the one above. Many of the maps I made were quite large, but I also created smaller, handheld maps. These made it easier for soldiers to use and carry around as they made their way across terrain in the various training areas during exercises.

Hey, this is pretty useful for my classes!

During my final year at UofT — which, depressingly, was fully online — my map making and GIS skills proved useful for some of my courses. Most notable was a Water Resources Engineering course, which covered topics such as water issues and legislation, reservoir analysis, urban drainage and runoff, deterministic and stochastic modelling, flood analysis, and more. Unfortunately, because we couldn't access the university's computer labs, our professor decided against including the usual ArcMap/GIS module.

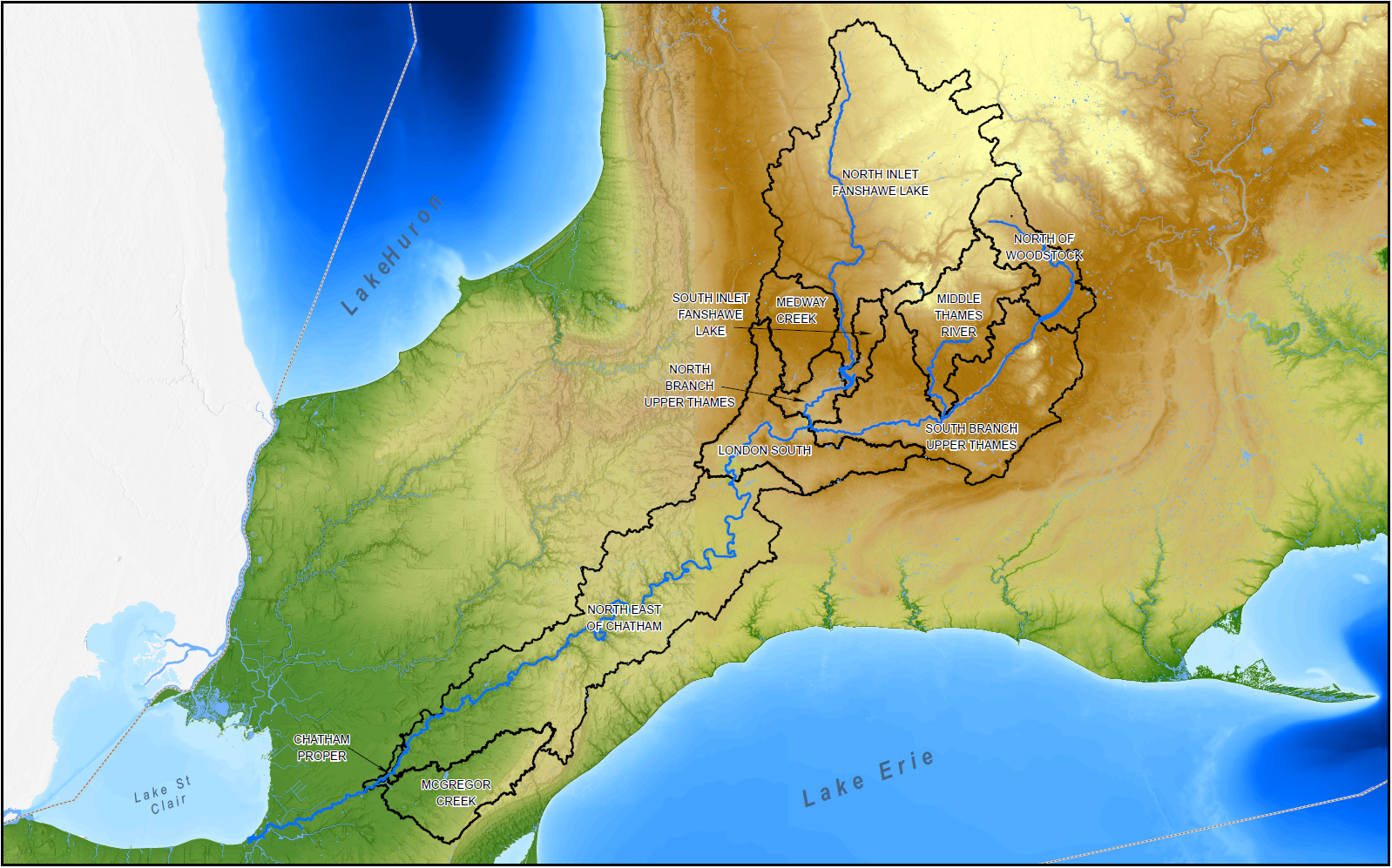

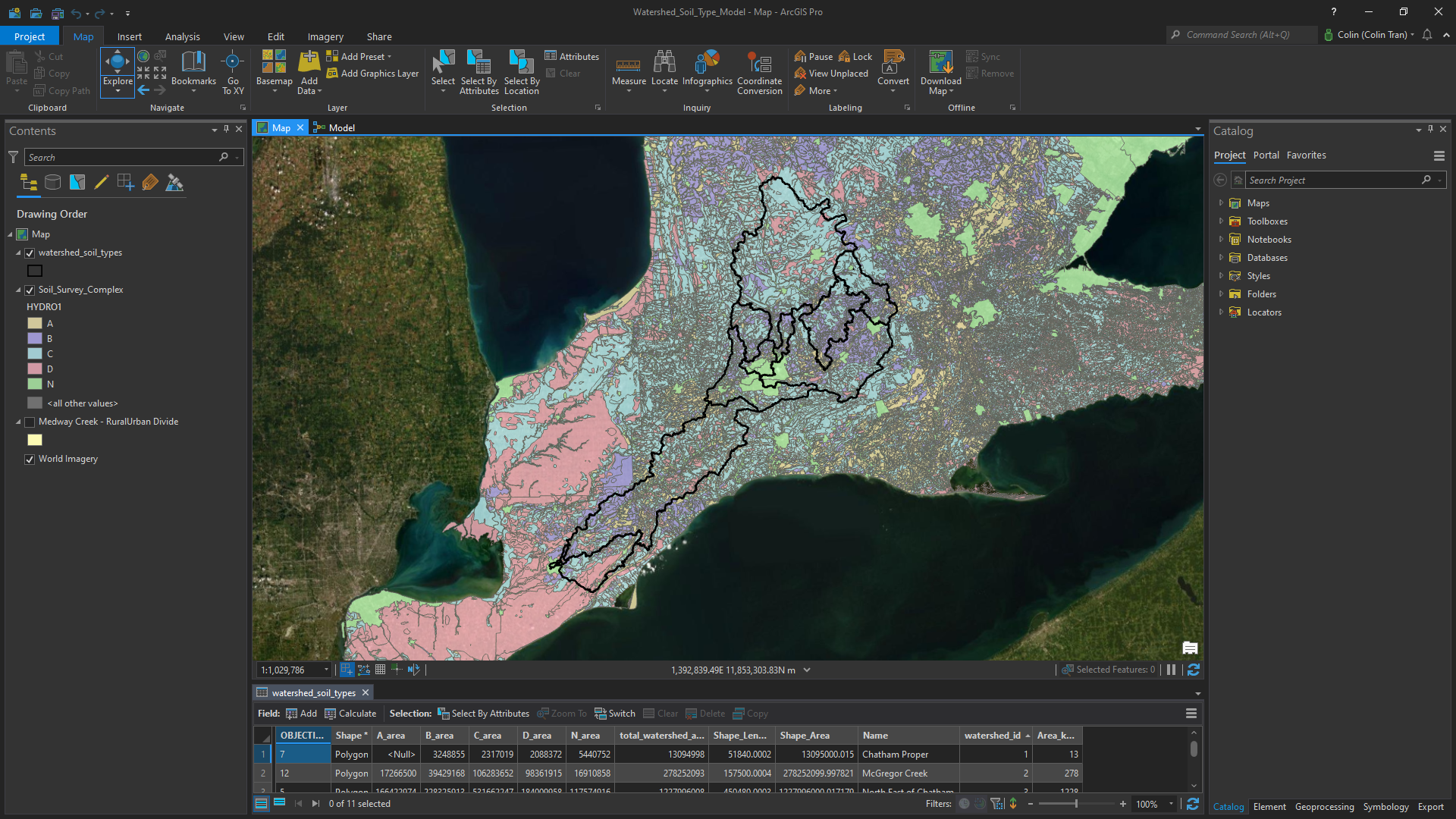

Nevertheless, I created maps where appropriate to supplement our group reports, and used the tools available to me to help with analysis. For example, a group deliverable required our team to estimate flood flows for a specific river, and I used ArcGIS to help calculate runoff curve numbers based on soil types for differnt subwatersheds. This allowed our group to have a slightly more accurate estimation of flood flows.

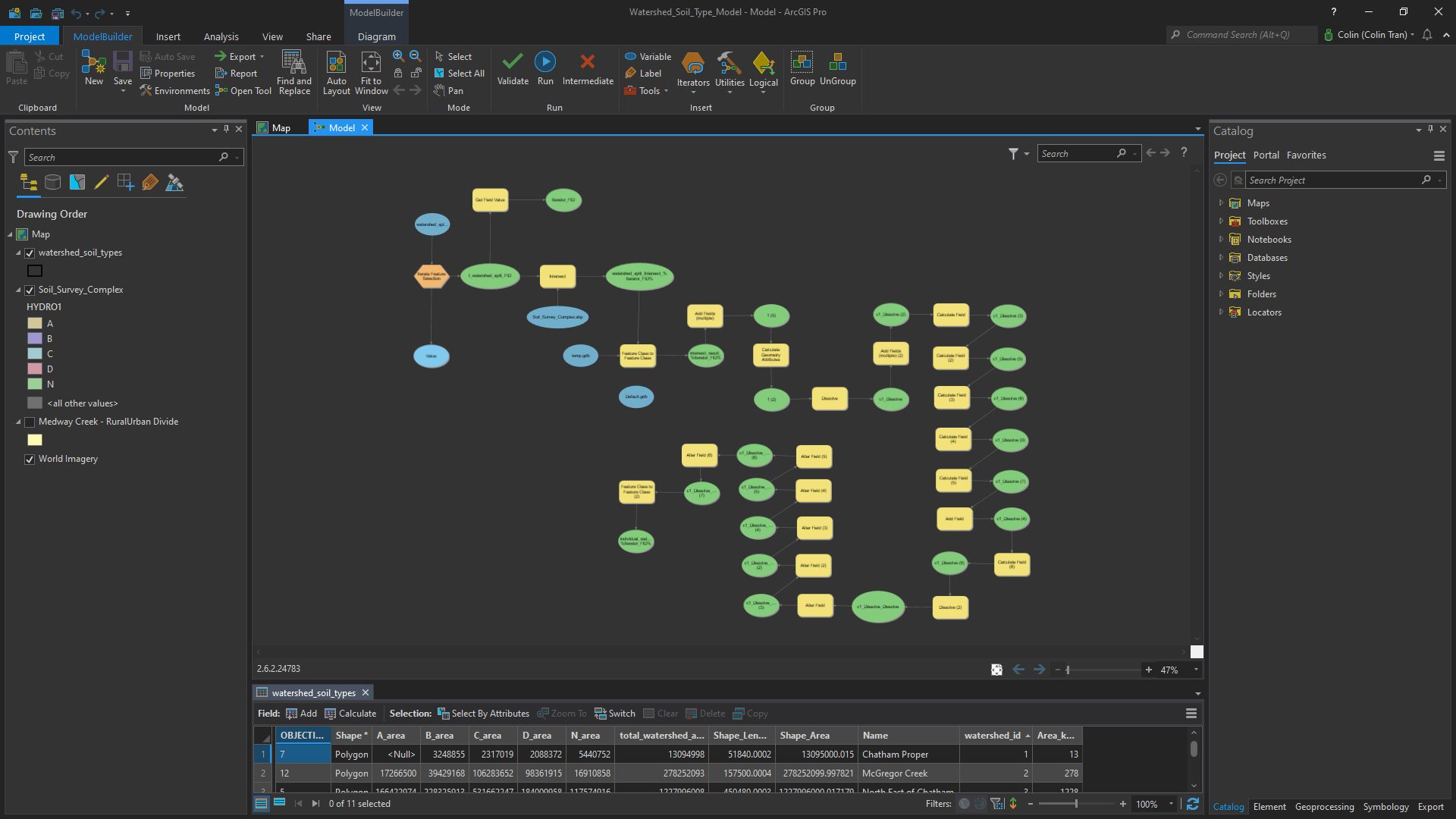

Left: Outline of sub/watersheds with the different soil types underneath. Right: The (slightly messy) model that I used to extract the % area for each soil type. This was my first time using the model builder in ArcGIS Pro!

Where to go from here?

Even though I've learned a lot over the years, I can't really call myself anything other than an amateur cartographer — even though I was paid as a soldier for some of my work. I personally believe that in the grand scheme of things, I know very little about mapping and geomatics, at least, when compared to my background and education in civil engineering topics. However, I think with the basic skills and experiences I've had with ArcGIS, I can realistically use the tools and software to assist in my engineering work.

Whether I work in water resources engineering, where dealing with GIS data is essential, or in the building sciences where geospatially enabled BIM data is extremely useful, I am confident that the foundation of skills that I have built will prove helpful. I hope, one day, to continue this journey and further develop what I have learned, in an engineering environment.